This essay was first published in Windmill: The Hofstra Journal of Literature and Art, September 2017

In the woods behind the house where I grew up, a two-hundred-year-old red oak tree keeps a silent watch over the untamed playground of my childhood. When the centenarian oaks were saplings reaching skyward, she was already an elder of the grassy hollow at the edge of the marsh. There were two other oaks of her size and breadth when I was growing up — massive, stoic stalwarts that required three or more adults to reach around the trunk. Both of these are gone now, lost in epic storms of summers past, the roots that anchored soil and generations finally giving way to the force of shifting winds. But this one old oak is still standing, her two main branches outstretched like a waiting grandmother, watching over red barns and green fields — fields that are always one season away from transformation to orderly, manicured subdivisions, or a return to wild, flowering prairie.

My siblings and I made a home in these woods, once the grazing pasture for the family farm, then simply the untended space between the neighbors’ houses.

My siblings and I made a home in these woods, once the grazing pasture for the family farm, then simply the untended space between the neighbors’ houses. “Neighbor” has a different look when you grow up in the country, though the heart of the concept is much the same. In my current home near Chicago, neighbor kids walk to school together during the week and play on opposing soccer teams on weekends. Their parents talk over shared fences while raking leaves or walking the dog. Our houses, separated by less than the circumference of the grandmother oak, were built at the turn of the 20th century. The oak savannah that anchored the prairie was harvested to construct the polished floors and gleaming archways in our homes. An American elm was planted in front of each new house, anointing the edge of the disappearing prairie as a neighborhood. The elms have been dying, from age and disease, although some are still glorious in their pre-planned majesty. The neighborhoods have matured around the old trees, and residents plant young saplings to replace stumps and sawdust when an elm is lost.

There are still no traditional marks of a neighborhood along the rural Wisconsin roads where I grew up —no sidewalks or stores, bus stops or traffic lights, at least not until you arrive in the nearest town several miles away. It is a community nonetheless. Some of the connection is familial, (we were distant or not-so-distant relations to many of our neighbors); some is survival (you want to be on good terms with at least one family with a snowplow or a towing cable); and some is simply the shared experience of life lived in the open, where seasons matter, where you have roots in the land.

Maybe we wake to ourselves in ordinary time, small moments that call out our names, that tell us we belong, at least for now.

My brother and I, the closest in age of four siblings, had a clubhouse among the tall grass and oaks below the hill. A long-fallen log served as headquarters for a secret spy and detective agency. Two close-growing trees formed the entrance to a mystical, time-bending realm. Sword fights and light saber duels were waged on stumps and rocks, the frogs and crickets singing background music for our theatrical battles. As we got older, we formed softball teams with the nearest playmates, our cousins. A trio of oaks between the woods and the cornfield neatly formed a diamond for bases. Behind second base was a timeworn boulder, a souvenir from glaciers that once carved the place that was now my backyard. I claimed this little space in the tall grass as my own, escaping when I could with a book or my journal, waking up, as children do, to the place in the world where they’ve landed.

As a child, I didn’t feel I had landed in my world, but rather emerged as another branch on an enormous tree that was already deeply anchored in place — a place both exceedingly small and exquisitely expansive. My father’s family had already farmed the land for over one hundred years by the time I appeared on the scene in the late 1960’s. My earliest childhood memories are fully formed snapshots of preschool days in the old farmhouse with my grandparents: my grandfather carefully weighing eggs on an ancient scale, holding them up to the light with long fingers twisted from childhood polio; my grandmother hollering down the laundry chute to him in the basement, requesting two eggs, whisking them into a batter in quick, efficient strokes; naps after lunch in the back bedroom, a breeze through the open window, the sheets always cool, even in summer; the mantelpiece clock chiming the minutes and hours of a day in the life of a four-year-old. These early memories are remarkable perhaps in that they are so ordinary — a regular day on a nameless farm, no drama or struggle or excitement to cause this indelible mark in my mind. Maybe we wake to ourselves in ordinary time, small moments that call out our names, that tell us we belong, at least for now.

When I did start school, I was in class with the same thirty kids for eight years, our last names familiar, our lineage established by previous generations. On Sundays my parents loaded four kids into the station wagon to drive the five miles to church, the same church where my grandparents were married, where my grandmother had traveled by horse and buggy as a girl each Sunday, warming her feet on a hot brick with her sisters. Every spring my grandfather would bring the trusty, sputtering Farmall tractor to till our vegetable garden. My brother and I would traipse through the uneven rows after the tilling, hunting for rocks and bugs and treasures long hidden beneath our feet. On the best days we might uncover an arrowhead, a lost and buried artifact from people that walked the land for thousands of years before our parents and grandparents, before all that seemed perpetual and solid and inherited. I imagined a Menominee child my age knapping arrowheads, sitting under the big oak on a spring day that seemed endless and immutable, like all childhood days. Who was I to love this land, to feel my roots growing deep with the oaks, when an ordinary spring day could turn up evidence that footsteps are fleeting, and belonging is relative?

We are wanderers by nature, the need to explore inscribed in our DNA. I loved the woods and wide skies of my youth, and also felt suffocated in all that space.

Whether we grow up as part of a large, grounded clan or in a small, itinerant family, it may be in the nature of childhood to seek what we do not have. We quibble with siblings for the last piece of cake, swallow our jealousy at a friend’s new toy, wander in daydreams far from our lives. Perhaps this must be the way of things. Why else would we leave the landscape of childhood — one that is as rich and even as a cornfield, or jutted and rock-strewn with pain —if we did not wonder, desire, dream? We are wanderers by nature, the need to explore inscribed in our DNA. I loved the woods and wide skies of my youth, and also felt suffocated in all that space. I dreamed about towns and cities, places with people and energy where the characters lived in the books I devoured from the public library. If I lived in a city, my detective agency would have endless mysteries to solve. I would have a best friend who lived next door. I would walk to her house whenever I wanted, and wouldn’t even have to knock. I would belong somewhere outside of my family, commanding the sidewalks with gangs of laughing kids on Big Wheels.

I really wanted a Big Wheel, that 1970’s emblem of childhood adventure and freedom. To have a Big Wheel, one really needs a sidewalk, or at the very least a paved driveway, as my imminently practical parents liked to point out. Riding at ground level with tractor tires and speeding pickup trucks on country roads was not an option if I wanted to survive to adolescence. I wasn’t as interested in actually riding the Big Wheel as I was in the community that seemed to surround them. My friends in town roamed the sidewalks of their close-knit neighborhood on Big Wheels, legions of stormtroopers and superheroes, the final word in freedom, the ultimate in cool. Sometimes in the summer, after what seemed like a long separation from town-based classmates and friends, our mothers got together to drink iced tea in someone’s kitchen, and for an afternoon I would be allowed into the hierarchy and abandon of a kid-ruled world. I made the mistake once of telling those friends that I wished I lived in the city like they did. Laughing, the much wiser and more sophisticated youth of our town of 2500 residents informed me that this was not a city. But there were sidewalks, and Big Wheels, and the ability to climb a fence and slip in the back door of someone’s house with the rest of the dirty, scraped-knee gang, clamoring for lemonade. I wanted that— whatever it was called.

The seeds of choice are scattered wildly, lavishly, and a child’s imagination is fertile ground for future blossoms and winding pathways.

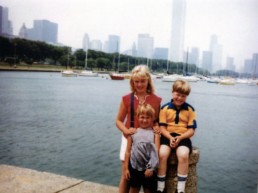

My childhood experience of actual cities, as opposed to small towns blessed with sidewalks and Big Wheels, was limited to occasional class field trips to the Milwaukee Public Museum, or a family outing to watch the Brewers play. Every couple of years my parents would load us up and drive the ninety miles south to Chicago. We would visit my mother’s aunt and uncle, who lived in a suburb, and make a pilgrimage to the Shedd Aquarium or the Museum of Science and Industry. The journey itself was always fraught with some kind of unwelcome adventure for my parents — say, a wrong turn landing us in a sea of traffic on Michigan Avenue with four unseatbelted kids bouncing around the back seat. But I would be humming with excitement, neck craned to see the canyon of skyscrapers rising around us, the rivers of people floating on invisible sidewalk currents. This was an entirely different world from my own, and although I was sure I would never live in a place as frantic and electrifying as this, I imagined what it might be like. The seeds of choice are scattered wildly, lavishly, and a child’s imagination is fertile ground for future blossoms and winding pathways.

There are choices we make that are careful and logical, the possible outcomes balanced in hand like smooth, polished stones. The stones we choose to carry will anchor us in place, or at times weigh us down. Those we cast into the pond still ripple and cast shadows, lifting our gaze now and then to the opposite shore. Other choices are as light and plentiful as autumn leaves, floating on air through changes in season. Through some combination of stones and leaves, I was drawn to one city, and then another, and finally to the place where I worked and fell in love and made a home for children. I am still planted here, but my roots are not deep. I sometimes feel like one of the new saplings, transplanted whole, roots wrapped loosely in burlap, replacing something that was lost, merely filling in a gap. I miss the wizened oaks, wide vistas across fields and marshes, the long arc of a country sky. I love the community, excitement and opportunities in the place where I live, the fulfillment of things wished for as a child. At the same time I long to breathe the air in the wide open space that I once found suffocating, to sit under the oaks in a whisper of wind instead of a rush of traffic. Perhaps it is also in the nature of adulthood to seek what we do not have.

There are choices we make that are careful and logical, the possible outcomes balanced in hand like smooth, polished stones. The stones we choose to carry will anchor us in place, or at times weigh us down. Those we cast into the pond still ripple and cast shadows, lifting our gaze now and then to the opposite shore.

For my children, this is home. They are sprouting here, flourishing. They arrive from school with friends in tow, clamoring for lemonade. They can, in fact, walk to friends’ houses, create adventures in a kid-ruled world, ride their bikes on the sidewalk under a canopy of elms. Some of our friends and neighbors have close ties and deep roots here, but most do not. Some of us landed here many years ago, and are still figuring out the view. Our children have become our roots — and our branches. We continue to grow, and the view improves.

We now reverse the childhood drive I used to take with my parents. We leave the stop-and-go traffic, the glow of streetlights and taillights, and head north to the country. My parents live in the same house on the same land, which has changed little in the decades since I’ve moved away. The kids explore the woods and the marsh, catch toads and climb trees. We camp in the summer, coyotes howling in silver fields under a full moon. In winter the new generation of cousins builds snow forts and toboggans recklessly. With red cheeks and bright eyes, they tell me how lucky I was to grow up in the country. Then, with smooth, polished stones in hand, they weigh what they love about life in their city, and what they would wish for somewhere else. And like falling acorns or dandelion down, the seeds of choice are scattered once again.

Childhood, too, anchors and falls, nourishes the unknown, abides, endures in lives that float, in seeds that travel far.

In every season, I pay a visit to the grandmother oak, lean on her massive trunk, crane my neck skyward to watch her leaves ripple against an endless sky. Last year, one enormous branch cracked in the wind and crashed to the ground. She may topple completely in the next big storm, or live for decades more. She is broken but persevering, perhaps out of habit, or perhaps drawing on the force of living things that have made this little hollow home, in every season, for generations. Thomas Wolfe wrote, “You can’t go back home to your family, back home to your childhood…back home to places in the country… back home to the old forms and systems of things which once seemed everlasting but which are changing all the time — back home to the escapes of Time and Memory.” When this tree falls, as I know she will, every child that has played in these woods will carry her home, in cell and memory, wherever home now may be. The oak will let go in time, wresting open a space that lets in the light, and a crumbling body will feed something new. Childhood, too, anchors and falls, nourishes the unknown, abides, endures in lives that float, in seeds that travel far.