This short story was originally published in The Examined Life Journal, Spring 2017, Vol. 5 No.2.

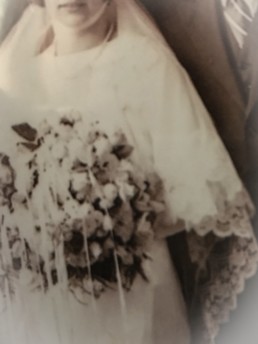

The third shift staff at Forest View Elder Care had forgotten about the open window in Room 316, leaving Hattie Hodges windblown, wet, and a little dangerous in one wild, untouched corner of her mind. An elegant thunderstorm had blown in from the west at dawn, silver lightning tracing cloud to cloud, sky to earth. She counted silently as her father taught her seventy-odd years before and waited for the thunder. The groaning rumble shook the wedding picture off the wall, shattered the glass, and overpowered the shift change chatter down the hall at the nurses’ station. Sooner or later one of them would come hustling in, close the window against the fullness of the storm, dry her papery skin with brusque efficiency. Hattie closed her eyes and hoped they would leave her a few moments longer, might allow the storm to do its work, shake free something forgotten with a crack of lightning or a gust of wind.

Hattie had always loved thunderstorms, even the violent ones with the power to change everything. She remembered her father’s stoic silence after the hailstorm of 1928, the crops tattered and flattened against the black, steaming earth. She understood the devastation written on her parents’ faces, but still couldn’t help inhaling the cool, clean air of the morning after the storm, the air that always beckoned her to follow, seeking something she could not yet name. She imagined herself floating just a little, swept along in the current of the creek beyond the barn, out over the fields of Wisconsin wildflowers, adrift all the way to the ocean.

She imagined herself floating just a little, swept along in the current of the creek beyond the barn, out over the fields of Wisconsin wildflowers, adrift all the way to the ocean.

There would be meetings and care plan revisions after this incident, specifically the line that allowed for an open window at night in the room of Hattie Martin Hodges, MD. When Charles was alive, he fought and charmed the staff, insistent on this particular detail of his wife’s care. And so the window stayed open for the first three years at Forest View until Charles, a renowned cardiologist, died of a cardiac arrest in the middle of Grand Rounds at the University of Chicago Hospital, and Hattie had to find inventive ways to advocate for herself. As a mid-century woman, doctor, and pioneer in her field, she was skilled in the art of creative negotiation, never hesitating to bend or break rules when needed. However, the paralysis and aphasia that were now her reality posed an even greater challenge than taking on old boys’ club department chairs or fighting for dwindling research funds. She discovered she still had a few hidden resources – a strong if unintelligible voice, movement in the finger closest to the call button. She found ways to keep the window open.

Hattie mourned Charles, of course, but half-welcomed the irony of their situation; it gave her something to think about. She always figured that Charles would die working. He was devoted to his wife, but the study of the heart, well, that was his real love. He succumbed in the arms of that mistress, a 78-year-old elder statesman in a room full of cardiologists unable to revive him. Hattie’s own exit from the medical world was a bit less dramatic, if only because it happened at home, without witness or heroic attempts at resuscitation. Charles, finally notified that Hattie had not answered her pages for most of the day, found her on the brick walkway behind their home, halfway to the garage on a blustery November afternoon. The Lake Michigan wind had summoned dried leaves that scratched the ground and collected around her head, her cropped, gray hair matted in the blood where she had fallen. It was big news at the hospital for some time, but no one ever came to visit her in the hospital, or during the failed attempts at rehabilitation, or in all the years at Forest View. Charles may have designed that as well; they were private people and protective of their profession. They both understood the sense of loss and failure she represented, the spectacle of a respected neurologist’s brain pockmarked in the aftermath of a stroke. It was a hailstorm of a different variety.

It was a hailstorm of a different variety.

Hattie watched as Eunice, the nursing aide for the day, crouched her small, round frame in the doorway and picked up shards of shattered glass, sparking the debate once more on the topic of the open window. Eunice had worked at Forest View for many years, and had refined the exquisite art of nursing home monologue. Hattie, in turn, had perfected her own ability to drift in and out of listening, letting a key phrase or random word send the working parts of her brain into reverie. Today the crash of glass and Eunice’s staccato prattle about windows and wedding pictures sent her memory flying back to a storm of another time, a night and a choice that changed everything.

A steady rain thrummed on the pitched farmhouse roof, masking the collective slumbering breath of the younger Martin sisters. The west window in the shared bedroom was open a crack, as it always was, and each gust of wind billowed the gauzy, white dress hanging on the closet door. Lightning flashes illuminated scalloped, lacy edges, the storm transforming the handmade wedding gown into a ghostly specter. Hattie knew there would be no forgiveness for what she was about to do, no gentle dawn the morning after the storm. Her mother would be the one to explain it to Elmer, averting her granite gaze from his trembling, calloused hands. Hattie was leaping into a blue-gray tempest of regret, but the call in her head was as clear as a June morning. There was no other way around this muddy path, this midnight escape; God knows she had tried. Her parents had only nodded politely when her teacher, Miss Hegeman, caught a ride all the way out to the Martin farm to plead Hattie’s case. They murmured obediently when even Father Hutmeier gave them his solemn opinion after Mass one Sunday morning. They had already done their part for their daughter’s “brilliant mind,” sending a girl to high school, only to cause this much trouble. They rejoiced when Elmer Schultz proposed, knowing Hattie would not refuse her childhood friend. His crooked smile and summer green eyes would keep her close to home and farm where she belonged, put an end to this nonsense.

The west window in the shared bedroom was open a crack, as it always was, and each gust of wind billowed the gauzy, white dress hanging on the closet door. Lightning flashes illuminated scalloped, lacy edges, the storm transforming the handmade wedding gown into a ghostly specter.

There was a sealed-off space in Hattie’s chest where her parents lived, their voices echoing “Nonsense!” off the walls of the empty chamber. The days and weeks after her rain-soaked journey had threatened to break her wide open, the taunts exploding out of her chest and wailing all over Chicago, exposing a nobody and a fraud. Over the years she had imagined fibrous bands braiding themselves over the fragile vessel, each achievement, each year adding one more protective layer. Even the layers, strong as they were, didn’t stop the vibrations just below the surface. They hummed in her blood when she graduated from medical school with honors, one of only two women in the class. They tapped on the sun-filled windows of her wedding day. They pummeled the roof with the loss of each pregnancy. At seventy, she believed that the walls perhaps were fortified enough to retire, and she could spend her days watching sunsets with Charles on that quiet beach in Florida they visited once, years ago. But one cold November day, she felt the walls crack and leak as she lay motionless on the ground, a slow soft chant soaking deep into the fibers of her being: nonsense, child, nonsense.

A change in Eunice’s tone alerted Hattie to the presence of visitors. Her gaze landed on two women in the doorway, and she took them in with one sweeping glance. No longer able to move or speak, she was still a facile observer, distinguishing details in the bearing and movements of the staff and other residents. She imagined the brains of her fellow neurological inmates, highways of electricity roadblocked with scars, once lush forest pathways now stripped clean of bark. She no longer had visitors of her own, but staff came and went from Forest View like the seasons. She studied the newcomers, determined their role and education by the way they flipped through the chart, the length and quality of interactions with the staff, their stride and demeanor as they made their way from the nurses’ station. An accurate conjecture soothed her pride when they inevitably introduced themselves in the singsong voice reserved for children, the elderly, and the disabled. Hattie hoped she had not used that voice with her own patients, but she didn’t know for sure. Some memories burrowed on the hazardous, muddy edges of old forest pathways.

Hattie studied the women conferring in the hall. The older woman, gray roots peeking out from an aging dye job, flipped quickly through the chart in her hand, pausing occasionally to push wire glasses up the bridge of her nose. An identification badge was clipped the wrong way to the lapel of a snug navy blue blazer, the style and fit at their best a decade before. She wore thick, cushioned shoes like the nurses, but the navy color had been carefully selected to match the blazer. After a few moments she sighed, snapped the chart shut and handed it absently to the younger woman, taking off at a clip down the hall. They were clearly teacher and student of something, Hattie mused, but after the hasty exit of the harried teacher, it appeared she would be in the hands of the student today.

Some memories burrowed on the hazardous, muddy edges of old forest pathways.

The young woman lowered a small table from the wall outside Hattie’s room and leaned her chin in her hand as she paged slowly through the chart. She was in her twenties, blonde hair pulled back in a neat ponytail. Hattie didn’t know what was written in a nursing home chart these days, but something appeared to have piqued the girl’s interest. When she finally raised the table and turned to make her way into the room, Hattie could see that the young woman was also pregnant. She didn’t have a lot of experience with pregnancy, in either herself or her patients, but she guessed this woman was five or six months along. Although she was young, she carried herself professionally, and pulled up a chair next to Hattie’s bed.

“Dr. Hodges, my name is Rebecca Roberts, and I am a fourth year medical student.” Hattie’s breath caught in her chest as she absorbed each surprise hanging in the air of that moment. No one had addressed her as “Dr. Hodges” in years, especially since Charles had died. All connection to the main river of her life seemed to have narrowed and dried, dammed by the stroke, leaving her to sit on the banks of a small tributary named Hattie, a woman she scarcely recognized. Hearing her professional name opened a trickle of something new – and old. She felt her atrophied and contracted muscles straighten just a little under the young woman’s curious gaze.

Hattie admonished herself for her lapse, for not recognizing the new visitors as physician and medical student. She knew it was 1997, thanks to dutiful day and date updates written by staff in large, bright letters on a small, white board in her room. It made sense that there should be more women in medicine now than she had been accustomed to during her own forty-year career, but the ivied walls of Forest View shut out most clues to the passing of time. Inside the fluorescent days and half-lit nights of her world, the physicians, who appeared periodically to perform cursory exams and sign off orders, had always been men. In this way Forest View mirrored the artificial luminescence of the days and years of her old life, a life lived in hospitals and lecture halls, a professional world inhabited by men. She had enjoyed a rich intellectual life, though it was understood she would need to work harder, give up more, and remain functionally alone in their company. It had taken her years to walk into a room with the gentle ease and clear-eyed grace of this pregnant medical student.

All connection to the main river of her life seemed to have narrowed and dried, dammed by the stroke, leaving her to sit on the banks of a small tributary named Hattie, a woman she scarcely recognized.

“I’m working with Dr. Keller today. I don’t think you’ve met her yet. She just moved to Chicago and has joined Dr. Roth’s group. She is going to see some other patients and then will join us a little later. From what I have read in your chart I know it is difficult for you to speak. I’d like to perform an exam if that’s OK with you. Maybe you could blink, or raise your eyebrow on this side if you’re all right with that.” The student touched Hattie gently on her left hand, her “good side,” although years of disuse had left that side weak and barely functional as well. She was impressed that this young woman had thought about her left eye as a means of communication. Hattie had forgotten about that herself. She met Rebecca’s steady gaze and gently closed her eye.

During the next twenty minutes, Hattie enjoyed the kind of thorough physical exam employed only by those in training and those that teach them. She realized that she might be the only resident at Forest View to appreciate an exam like this, and tried to remember how many students and patients she had put through these paces herself. Hattie delighted in the structure and the rhythm of the neurological exam: the subtle or exaggerated response of reflexes beneath the rubber hammer, the steady vibration of a tuning fork, the lines of demarcation where sensation was lost. Hattie would draw maps in her mind as she examined a patient, each new finding a clue to the puzzle beneath the surface. As technology had advanced she found it harder to generate enthusiasm in her students for the elegance of the exam, their attentions turned instead to the ease and accessibility of shiny toys like MRI scanners. Even before her sudden departure from the medical world, she had begun to wonder if she might be one of a dying breed.

The student had been well trained, thought Hattie, and even seemed to enjoy the rhythm and dance of the exam herself. Hattie knew there was no particular reason to perform such a thorough physical exam for her own benefit. Aside from the slow stagnation of her body and mind as the years flowed by, there had not been any great changes in her condition for a long time. The student would report her findings to the frayed attending physician, receive a few dispassionate comments, and the two of them would agree to continue the current plan of care. Still, Hattie felt like a teacher again, even if all she could do was allow herself to be the patient. Rebecca’s steady hands had found an invisible crack in the timeworn seawall of Hattie’s pride, and the tide was rising.

Rebecca’s steady hands had found an invisible crack in the timeworn seawall of Hattie’s pride, and the tide was rising.

The gentle stream of Rebecca’s voice flowed and paused while she examined her patient. Both women felt a current of recognition, a familiarity they could not name. Hattie marveled at Rebecca’s ability to maintain a one-sided conversation that still felt somehow whole. She asked questions and paused, comfortable in a silence that allowed them both to ponder the answers, even if they were never spoken aloud. Hattie learned a little about her: she planned to go into Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, her husband had matched into a surgical residency, and the baby, a girl, would be born just after graduation. Hattie tried to imagine what Rebecca’s story would have looked like in the trajectory of her own life and career. Her childlessness was a wound she had mourned privately and closed off carefully. As the years passed she had generally convinced herself that it was for the best anyway, as she could devote her full energy and attention to patients and career. She had made a name for herself. The rain-soaked farm girl from Wisconsin was somebody.

A small silence in their conversation was broken with the abrupt return of Dr. Keller. “OK, Rebecca, I’ve rounded on the others. Tell me about, uh, Mrs. Hodges.”

“Yes, Dr. Keller. Actually, this is Dr. Hodges. There is an interesting note about her in the social work section of the chart. She graduated from my medical school in 1946. I’m going to look up her work in the library when I get back to campus.” Rebecca met Hattie’s eyes and gave her a knowing smile.

Mary Keller arched an eyebrow and looked past the open chart at her patient. Hattie had not had much opportunity to observe the middle-aged woman, but now met her haggard gaze. She watched the doctor’s face change slightly, an almost imperceptible twitch in her jaw, a different sort of connection in her eyes. Rebecca had fastened herself to Hattie’s beginnings, to the young woman who had learned her own strength, her past celebrated on a dusty pedestal of achievement polished by the next generation. Mary Keller had no time for celebrations, least of all the past. She was prostrate to the present, and was staring into her own frightening future – a sinkhole of enormous proportions. She saw herself in Room 316, tossed and stranded by a ceaseless tide. Here she would reclaim the time she had lost – a forsaken eternity at her feet – in solitary contemplation of a fractured family, a frozen life, and the twilight of her own mediocrity.

Her childlessness was a wound she had mourned privately and closed off carefully. As the years passed she had generally convinced herself that it was for the best anyway, as she could devote her full energy and attention to patients and career. She had made a name for herself. The rain-soaked farm girl from Wisconsin was somebody.

“I would love to know what she experienced as a woman physician in those years,” murmured Rebecca. “How do you think they were able to manage work and a family back then?” She turned toward her teacher, unconsciously rubbing the top of her belly. Hattie watched the changing skies of response on the physician’s face, a breath caught, an answer changed. A well-rehearsed smile spread across her face, sparing the eyes, as she faced her student. After a hurricane or two, she had learned to shutter the windows, ride out the storm when evacuation seemed futile. This new generation needed to learn to do the same.

“I can’t speak for Dr. Hodges, although I agree, it would be fascinating to know. The most important thing is just to keep going. Don’t overthink it. There are lots of us who have done it, and you’ll do it, too. It’s hard sometimes, yes, but the kids will learn that you can’t always be there for everything. We’ve chosen to be physicians, so we should be physicians. Women should choose something else if they’re not prepared for that lifestyle. Take some time off when the baby’s born, but not too long. You can get derailed really easily. Oh, and make sure you find good help. You need to find someone who is flexible enough to work around your hours.”

Mary Keller signed off a few pages of the chart, closed it with authoritative efficiency, and checked her watch. Hattie watched Rebecca chew her inner lip, her face otherwise unreadable. “OK, Rebecca, anything else I should know about your exam before we go?”

Rebecca started, then stopped, glanced at Hattie, changed her mind. “No, Dr. Keller, nothing of note.”

Mary Keller turned on her heel and strode back toward the nurses’ station. Rebecca looked after her for a moment, then leaned over the bed and squeezed Hattie’s hand. “Thank you, Dr. Hodges. It really was a pleasure meeting you.” She glanced out the window and followed her teacher out of the room.

She walked the shores of that creek in memory, and found the banks littered with stones and casts of heavy things remembered or forgotten, ordinary and precious.

Hattie gazed out at the western sky, the window now closed and locked. The rain had stopped for the moment, but pewter clouds promised a new round of storms. Hattie thought about Rebecca’s baby, floating and secure, the paradox of possibility already inscribed in her genes. She remembered her own childhood daydreams, the creek behind the barn beckoning her to float away under a summer sky. She walked the shores of that creek in memory, and found the banks littered with stones and casts of heavy things remembered or forgotten, ordinary and precious. She longed to show them to Rebecca, to touch their solid forms, to remember what was left behind in raging storms and clear summer days.