All photographs were taken on a February 2018 visit to the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, Illinois.

I cannot think of a better way to spend a frigid Sunday afternoon than spelunking the grand caverns and winding passages of a museum. Chicago museums offer a delicious menu of free days for the cooped up, winter-weary residents of our frozen state. Our family tries to keep a rotating membership between the museums, but the free days of February offer an escape for a few hours to the magical underwater world of the Shedd Aquarium; the quiet, ethereal palace of the Art Institute; or the hands-on, high-tech wonderland of the Museum of Science and Industry.

My favorite, though, will always be the Field Museum, Chicago’s century-old monument to natural history. I love walking up the wide, marble staircase and passing through the Greek columns to the stately, echoing entrance hall. We stride over fossils on the limestone floor while statues of the four muses – Record, Research, Dissemination of Knowledge, and Science – watch from above with vacant, all-knowing eyes.

“Don't go to a museum with a destination. Museums are wormholes to other worlds. They are ecstasy machines.”

-- Jerry Saltz

There are few bells and whistles here. Instead of “push me” lighted buttons, digital displays, and blaring audio exhibits, there is dim lighting, hushed tones, and informational text that a person actually has to linger over and read. It can feel like a cathedral at times. At other times it is a raucous echochamber of young minds and bodies, such as the overnight camp experience among the dinosaur bones with hundreds of scout troops. (I left that one to my husband during the Cub Scout era). However, I did once chaperone a fifth grade field trip here, shepherding a group of tittering boys through exhibits of buxom fertility statues and taxidermied animals with names like “wild ass” and “dik-dik.” I heaved a sigh of relief as we boarded the school bus home, having not lost a single one of them in the near-total darkness of the mummies or the succession of mass extinctions.

Even when we travel with our own little family, the day begins with excitement but is soon punctuated with the need for food and bathroom breaks, tired legs, and waning attention spans. Every time we go I say I am going to come back by myself one day and spend hours basking in lengthy explanations, dusty dioramas, and the smell of old things. My friend Mark, a paleontologist who studies the evolution of marine mammals, once took us behind the scenes at the Smithsonian to look at the fossil collection. I was giddy as he showed us the skulls of ancient whales, dinosaur femurs, and drawers full of vertebrae and teeth. The room seemed to pulse with the energy of things that remained, that had been found, that became a piece of something larger and wider than their own separate parts.

The room seemed to pulse with the energy of things that remained, that had been found, that became a piece of something larger and wider than their own separate parts.

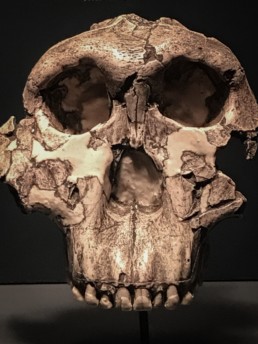

I have been known to photograph the same trilobite fossils, Ice Age skeletons, cultural artifacts, and ancient shards many times over. I stand in the shadows of dimly lit rooms, transported to impossible places over a timeline I cannot grasp. I want to feel the rough edges of hoary rock, listen for the whispered voices of the long-dead, trace the cracks and fissures and stitches until my eyes blur and tire. A photograph may be as close as I can come to possessing the treasures for myself, which is, of course, precisely the opposite idea of a museum. Instead I will stop for a few ponderous moments, collecting questions instead of artifacts, and taking home my wonder at the vastness of it all.

“I've become like one of those people I hate, the sort who go to the museum and, instead of looking at the magnificent Brueghel, take a picture of it, reducing it from art to proof."

-- David Sedaris, Let's Explore Diabetes with Owls

I am as small and insignificant and connected and alive among these relics of the long dead as I am beneath a canopy of stars. The problems that I turn over in my head like a complicated gemstone will never have the longevity of these broken bits of pottery; or the nameless child whose bones were found in the dust of a vast desert; or the insignificant beetle who will hover forever in honeyed amber. Perhaps the ancient potter smoothed out her own ruminations in river clay and ocher paint; perhaps she simply hummed as she worked in the morning sun. The youth we call Turkana Boy may have been mourned in some manner by his wandering troop; perhaps his bones were left to be scavenged, the weight of them no longer useful. And it is likely that no other living creature witnessed the beetle’s fall into sticky resin hundreds of millions of years ago, suspending its struggle in a golden grave. How we underestimate the significance of insignificant moments; how little we understand of eternity.

How we underestimate the significance of insignificant moments; how little we understand of eternity.

What will the prized possessions and throwaway things of our own time mean to those who may find and preserve them a hundred generations from now? They too may stand in quiet contemplation of the noble genius of simple tools; the cunning brutality of past wars and conquests; the wonder of how much has changed, and the gasping realization of how much has not. Will they extract understanding like DNA, grasp the things that mattered, even if we ourselves did not?

In the half-breath of my own lifespan, I will freeze a few fleeting moments in the loamy sediment of memory, perhaps preserve a few thoughts or ideas with the semi-permanence of words and images. And then those too will pass away, back to the earth that heaves and settles, the new and unknown sprouting from bones and ash. I will wander this earth with a little more reverence, my feet planted softly on sacred ground.